Earth is due to pass through a trail of debris left behind by Halley’s Comet in 985 B.C.E., which may cause a slight bump in the number of meteors ahead of the Eta Aquariids’ peak next week.

Halley’s Comet was last seen in our skies in 1986. Credit: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology

When Halley’s Comet flies through the inner solar system every 75 years, it leaves behind a trail of dust and debris. Every year, Earth passes through that trail — once in May and again in October. Each time it does, we see a stunning meteor shower: the Orionids in October, and the Eta Aquariids in May.

This year, the Eta Aquariid meteor shower reaches its peak on May 5, which is generally when the most shooting stars can be seen. But this year, something special may happen, as two days earlier, on May 3, Earth is projected to move through a particular trail of debris shed by the famous comet in 985 B.C.E. This could cause a second small peak in the shower — and also offers a chance to watch some pretty ancient dust spectacularly burn up in our atmosphere!

An historic stream

Every time a comet passes through the inner solar system, it is heated by the Sun, causing it to spew dust and gas. These generate the stunning tails we see. After it’s liberated from the comet, some of that dust continues to orbit the Sun along the same path as its parent comet, which is how we can predict exactly when Earth will run into these streams each year to create meteor showers.

But over time the solar wind, coupled with gravitational effects from the worlds of the inner solar system, can cause these streams to distort and “wander” in their orbits. Astronomers can use computer modeling to determine just how different streams from various passages may behave over time, and calculations show that this year, we’re due to pass through a particular “thread” left by Halley’s Comet from some 3,000 years ago, when it appeared in the sky in 985 B.C.E.

How to see Halley’s meteors

So, how can you catch sight of shooting stars making their final journey after floating in space for three millennia? Fortunately, it’s easy, and the mild May weather should even make it quite enjoyable.

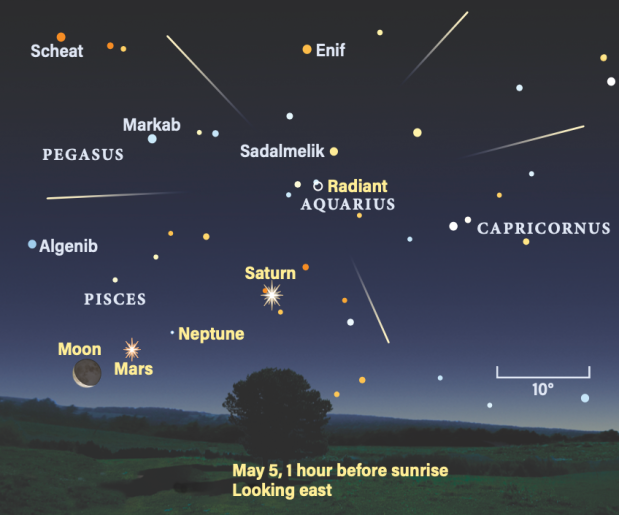

On Friday morning, you’ll want to be up early. Look east starting about two hours before sunrise, when the shower’s radiant, located in Aquarius the Water-bearer, is 15° above the horizon. Within an hour (so, by an hour before sunrise), the radiant has nearly doubled its altitude and is 25° high. You can easily locate the radiant by looking almost directly above and just slightly right of magnitude 1 Saturn, the brightest point of light in this region of the sky.

Once you’ve located the radiant, it’s time to move away from it — turn your gaze about 40° to 60° to one side or the other, so you’re looking more northeast or southeast. These are the places in the sky where you’re more likely to see the long, streaking trains of bright meteors as they skim through our atmosphere. You won’t need any special equipment, just your eyes and some patience. You can expect to see perhaps a dozen or so meteors per hour if our passage through this historical stream causes a slight bump in the number of expected meteors, which is expected to peak on the 5th at about 50 meteors per hour.

Just know that any meteors you do see, however many or few, are the same pieces of space dust left behind by Halley’s Comet some 3,000 years ago — a unique connection to history!

You can check out our weekly Sky This Week column for more details on how to catch the Eta Aquariids’ official peak in just a few days, on Monday morning. Or, read Sky This Month for a full listing of everything to expect in the sky for the month of May!