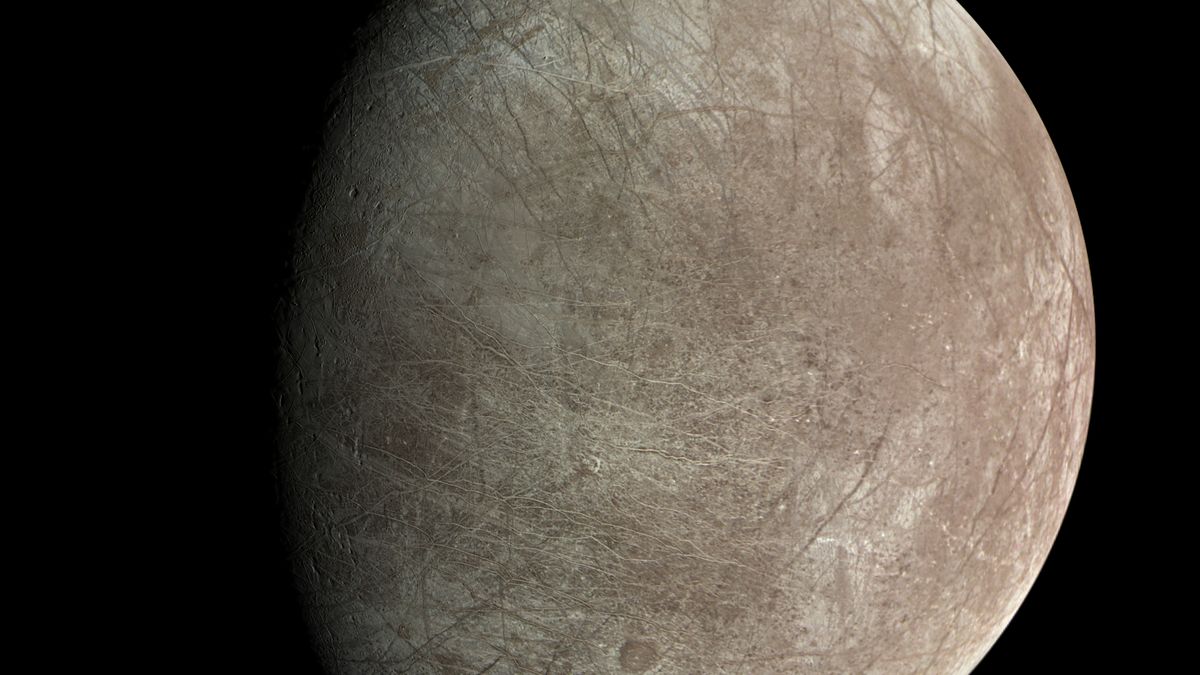

When NASA’s Juno spacecraft performed its closest approach to Jupiter‘s moon Europa in September 2022, it captured evidence not only for pockets of briny water connected to the world’s deep subsurface ocean, but also for potential scars formed by towering plumes of water vapor — and it caught that evidence on camera

The majority of imagery from the Juno mission is taken by an instrument called JunoCam, which scientists revealed was able to take four high-resolution images of Europa’s surface as it raced past the icy moon at an altitude of just 355 kilometers (220 miles). The spacecraft also employed its Stellar Reference Unit (SRU), which is normally used for imaging faint stars, to help Juno navigate. On this occasion, however, the SRU’s low-light capabilities were adapted to take one image of the night-side of Europa. This is the side that shines only with light reflected off the cloud-tops of Jupiter — we call it “Jupiter-shine.”

Related: NASA’s Juno probe captures amazing views of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io (video)

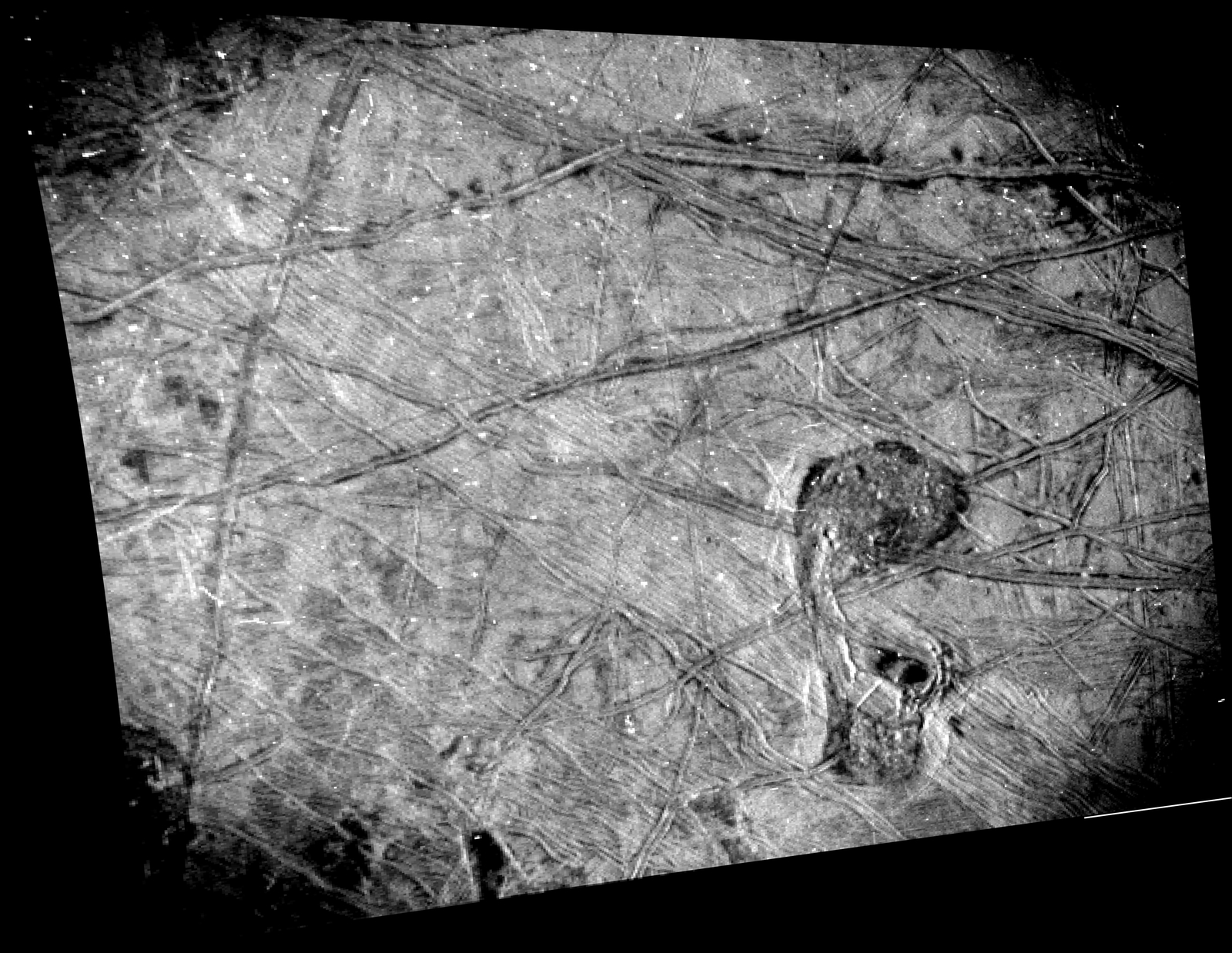

The SRU found an unusual feature that has been nicknamed “the Platypus” because of its shape. Formally speaking, it is what’s known as chaos terrain — a jumble of ice blocks, ridges, hummocks and ruddy-brown stains. Chaos terrain has been imaged on the surface of Europa since the days of the Voyager missions, and planetary scientists suspect that such regions may be areas where briny liquid seeps to the surface, partially melting the icy crust.

The platypus is huge, spanning 37 kilometers by 67 kilometers (23 miles by 42 miles). Because Europa’s icy surface tends to smooth itself out over geologically short time spans, erasing surface features such as craters, then the Platypus must be one of the youngest features on the Jovian moon.

“These features hint at present-day surface activity and the presence of subsurface liquid water on Europa,” said Heidi Becker, who is the SRU’s lead co-investigator at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in a statement. Becker goes on to suggest that the Platypus will be a primary target for both NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which launches later this year, and the European JUICE mission, which is already on its way to Jupiter.

Fifty kilometers (31 miles) north of the Platypus are potentially even more exciting features: a set of double ridges flanked by dark stains on the surface. Such features have previously been seen elsewhere on Europa, and are believed to be an origin point for plumes of water vapor that spurt up into space, reaching heights of 200 kilometers (120 miles).

The elusive plumes have been somewhat controversial ever since the Hubble Space Telescope first caught sight of them in 2012. However, unlike Saturn‘s moon Enceladus, where plumes are a predictable and common occurrence, Europa’s plumes have been somewhat spotty, leading some researchers to doubt plumes exist at all on Europa The discovery of trenches, somewhat analogous to the tiger stripes on Enceladus— the points of origin for the world’s plumes — will provide Europa Clipper and JUICE with regions to target in their search for the plumes on Europa as well.

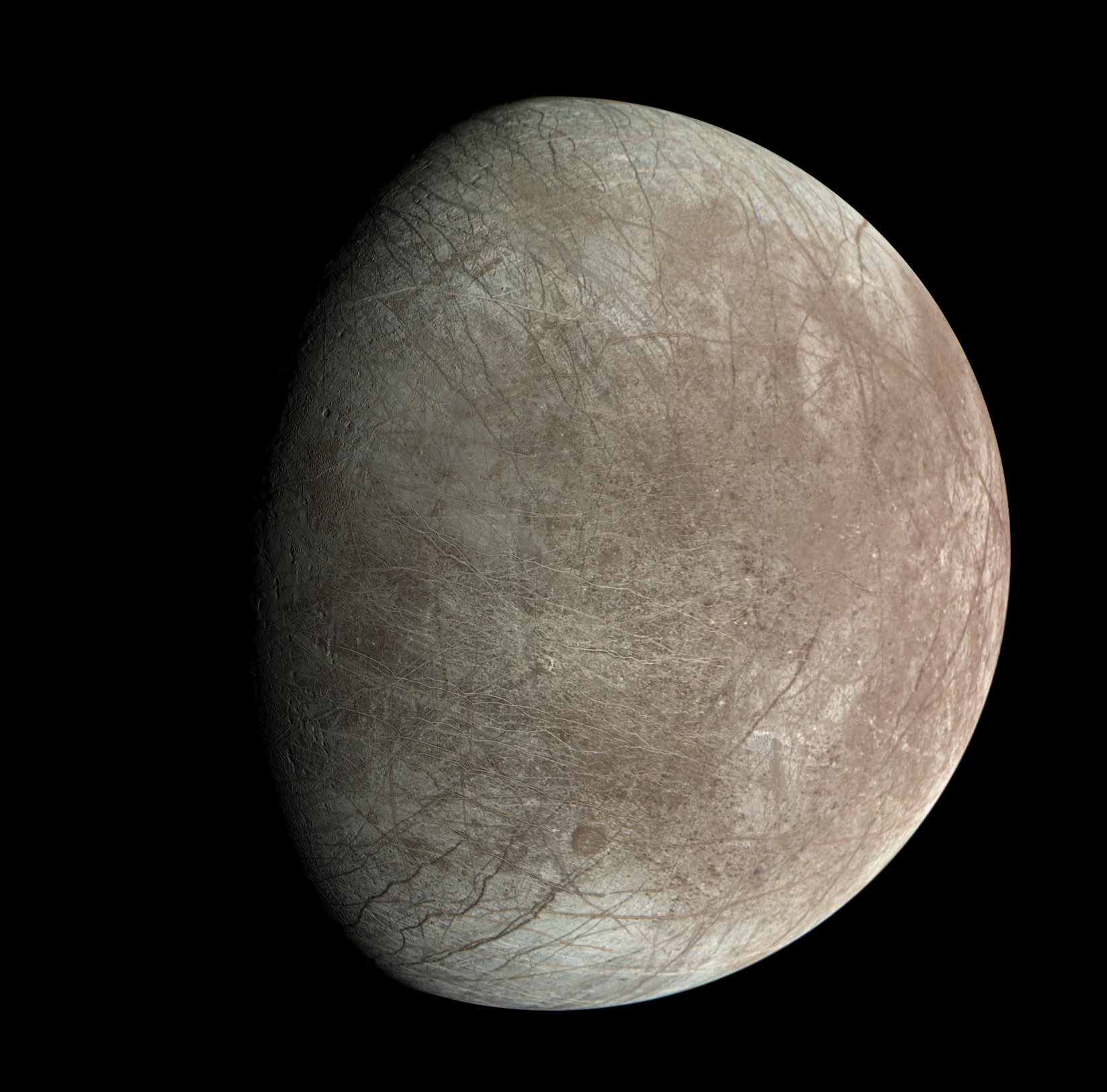

However, Juno has also found powerful evidence that these features, and the surface as a whole, are shifting beneath Juno’s metaphorical feet. Scientists call it “true polar wander,” which means the geographic locations of the poles have meandered across the moon as the icy crust effectively floats on the subsurface global ocean.

“True polar wander occurs if Europa’s icy shell is decoupled from its rocky interior, resulting in high stress levels on the shell, which lead to predictable fracture patterns,” said Candy Hansen, who is a Juno co-investigator at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona.

Juno imaged these fracture patterns in the form of steep-walled, irregularly shaped depressions between 20 kilometers and 50 kilometers in size (12 miles to 31 miles).

“This is the first time that these fracture patterns have been mapped in [Europa’s] southern hemisphere, suggesting that true polar wander’s effect on Europa’s surface geology is more extensive than previously identified,” said Hansen.

The results of JunoCam’s images of Europa during the flyby were published in March in The Planetary Science Journal, and the SRU results were published in December 2023 in the journal JGR Planets.